By Dawn Byron Hutchins for Connecticut Explored

At the height of shade tobacco’s popularity in the first half of the 20th century, more than 16,000 acres of this premium cigar wrapper tobacco were under cultivation in Connecticut. The introduction of such a labor-intensive crop to Connecticut’s economy drew migrant labor from the South, the Caribbean, and even small towns in Pennsylvania.

The search for a reliable labor source led to an ongoing relationship of more than 50 years between growers and a special group of Southern workers: students. For these young people, a summer away from their Southern homes was an opportunity to earn money for their education, enjoy freedom from parents, and get some relief from their segregated existence. Among the thousands of black Southern students who seasonally came north was a young Martin Luther King Jr.

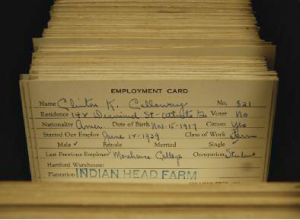

Cullman Bros. employment cards. Clinton Calloway (1917-1999) graduated from Morehouse College in 1941 – Dawn Byron Hutchins

Tobacco Growing an Early Colonial Crop

According to probate records, Connecticut farmers grew broadleaf tobacco (shade tobacco would come later) as far back as the 1600s. Originally brewed as a beverage or smoked in pipes, by the late 18th century tobacco was being hand rolled into cigars in family workshops. After the Civil War, farmers faced competition from foreign-grown tobacco, yet increasing tariffs did little to protect them. When a thinner and superior cigar wrapper was imported from Indonesia, the challenge to the domestic cigar tobacco market could not be ignored.

In an attempt to help farmers grow a more competitive product, the US Department of Agriculture began experimenting in Florida with tropical tobacco varieties. By 1899, W. C. Sturgis, a botanist in Connecticut, was successful in growing Sumatra tobacco from seed and reproducing the thinner leaf. Marcus Floyd, the USDA’s leading tobacco expert at the time and a Florida native, came to Connecticut to oversee the first crop of this experimental tobacco known as shade tobacco. The product proved equal to the imported leaf.

Fifty acres was put into the production of shade tobacco in 1901. Following the first flush of success, several wet growing seasons dashed the hopes and finances of many small farmers, who ended up selling out to larger growers. Still, by 1910 shade tobacco was well established in Connecticut, with hundreds of farmers cultivating it.

Cultivating Tobacco in Connecticut

Connecticut farmers were used to the simple cultivation process and single harvest of broadleaf tobacco that was most commonly used as filler in cigars. Shade tobacco is more complicated. The growing season begins in May with weeding and transplanting seedlings in long rows. As the plants grow they are fastened to guide wires, and then cloth tents are spread over them to increase humidity, protect the tender plants from direct sunlight, and maximize the short New England growing season.

The remainder of cultivation takes place by hand. Field workers spend weeks in high humidity and extreme heat moving among the rows, pulling off shoots and tobacco worms. Multiple harvests of leaves are brought to sheds, where workers—most of them female–sew the leaves together to string on wooden lath. The laths are then hung up in the rafters of the slat-sided tobacco barns or sheds to cure. After curing, the tobacco is moved to sorting sheds and warehouses, where processing continues throughout the rest of the year.

World War I Diversifies Tobacco Workforce

Until the advent of World War I, Hartford-area whites, both residents and immigrants, filled the need for seasonal labor. When war broke out in Europe, these workers took jobs at munitions plants, which promised higher wages, and many immigrants returned home to serve in their own military. New immigration was hampered by the restrictive immigration laws of the era.

In an attempt to find labor, the Connecticut Tobacco Company placed an ad in the New York World in December 1915 for 500 girls to work as sorters, offering free transportation. This led to a public relations disaster. Emmett J. Scott, an advisor to the US Secretary of War and secretary-treasurer of Howard University, included the incident in Negro Migration During the War:

The planters…promiscuously gathered up 200 girls of the worst type, who straightaway proceeded to demoralize Hartford. The blunder was speedily detected and the employers came back to New York seeking some agency which might assist them in the solution of their problem.

The National Urban League, already serving as a clearinghouse for northern migrants, helped growers recruit workers using black newspapers such as The Chicago Defender that also circulated in the South. A trickle of southern blacks responded to advertisements and moved north with their families. By 1920 seven black families from Georgia and Alabama were renting tobacco company housing in Granby alongside Polish and Lithuanian immigrants. These sources did not provide sufficient labor.

A Solution to Labor Shortage: Southern Black Students

Male students from Virginia and their chaperones, Hartman Tobacco’s Camp, Buckland Manchester, 1942 – Dawn Byron Hutchins

Marcus Floyd, by 1911 president of the Connecticut Tobacco Company, “offered a solution for this difficult problem through the further importation of negro labor,” Scott notes. “The response to this suggestion was not immediate, because New England had never had large experience with negro labor. …Because of the seasonal character of the work, an effort was made to get students from the southern schools by advancing transportation.” According to Charles Spurgeon Johnson in The Negro Population of Hartford, Connecticut, “The material for this first experiment was sought in the schools of Virginia, North Carolina, Florida, and Georgia. More than 1,400 students were transported to the State of Connecticut.”

The National Urban League introduced Floyd to Dr. John Hope, the first black president of Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia. Students from historically black colleges such as Morehouse were already accompanying their professors north to work seasonal service jobs at New England resorts. The transition to working shade tobacco provided more students with jobs that helped them pay their tuition and removed them, for a time, from the escalating racial tensions at home. College students provided Connecticut growers with an English-speaking, educated work force. These students also appealed to employers because, accustomed as they were to the way blacks were treated in the South, they were not as likely as northerners or immigrants to agitate for better working conditions. Also, as temporary seasonal workers they would, theoretically, not have much impact on the communities in which they worked.

Floyd first recruited Morehouse students for the 1916 season at Connecticut Tobacco’s Hazelwood plantation on the Windsor/East Granby border. According to an August 16, 1916 article in The Hartford Daily Courant students were paid $2.00 per day, and they in turn paid $4.50 per week for their room and board. Working from June 1 to September 1, students could clear as much as $100 (about $2,000 today) after expenses. The same article reported, “The Connecticut Leaf Tobacco Association considers the importation of Southern help to have passed the experimental stage.”

Recruiters sought student workers from other schools, too. Students from Florida A&M, Morris Brown College (Atlanta, Georgia), Howard University (Washington, DC), Livingstone College (Salisbury, North Carolina), and Talladega College (Talladega, Alabama) also worked tobacco in Connecticut throughout the 1920s and ‘30s.

Accommodating Student Laborers, in Work and Leisure

Corporate growers were able to minimize their labor problems by creating residential camps on their tobacco plantations. A Morehouse dormitory was built on the Simsbury/Granby border in 1936; Martin Luther King Jr. spent the summers of 1944 and 1947 there. By building dorms or using abandoned Depression-era Civilian Conservations Corps camps, growers made their labor supply wholly dependent upon them.

Tobacco-worker housing in Simsbury, similar to the dormitory where Martin Luther King, Jr. spent the summers of 1944 and 1947 – Dawn Byron Hutchins

Providing housing also enabled recruitment of southern black high school students. One legendary recruiter was black school principal Henry Lawrence Summerrall, who modeled his rural youth program in Central Virginia on the one Morehouse College (which he briefly attended) established in 1916. From 1941 to 1976, more than 12,000 high school students ages 13 and up made the trip north to work for the Hartman Tobacco Company at Camp Buckland for boys in Manchester and (after 1949) Camp Stewart for girls in Windsor.

While work in the fields was long and hard, efforts were made to provide residential students with religious and social opportunities. As a bonus, these also often served as good public relations for the tobacco companies. A rally in 1929 arranged by the Hartford YMCA at the AME Zion Church brought students from plantations in Tariffville, East Windsor Hill, Simsbury, Poquonock, and Windsor to meet Hartford residents.

One student from Lynchburg, Virginia, recalled in 1952: “We were taken into Hartford on a company bus (looked like a school bus) and we parked down in what is now known as the Front Street section…my brother and I spent our time going to the movies,” wrote William S. Spencer, age 15. Other students remembered going to a shopping center. Camp managers also planned end-of-season trips to Riverside Park in Agawam, Massachusetts, to send students off on a positive note, in hopes that might benefit the next year’s recruitment effort.

Opportunity of Tobacco Field Work

High school guidance departments also steered students toward work in Connecticut. For black students unable to secure summer jobs in retail or service industries, tobacco was “really the only job opportunity,” according to a group of female students from Plainville. These students, including Anita Baldwin, Taffie Bentley, Norene Robinson, and Gail Williams, responded to flyers distributed at their school in mid-1950s and were hired to sew in the sheds. The work left them at the end of the day covered in tobacco juice and tar. Their recollections showed that tobacco was not a summer job of choice:

And it was most embarrassing, so when you got off the bus…we used to run all the way home because we didn’t want anybody to see us …once we got home at 5, it was still an hour to get clean before you could feel comfortable to sit at the kitchen table and eat your dinner.

But for students with few economic choices, summer tobacco work provided both opportunity and motivation. “The work was hard and unbelievable at times but my learning experience away from home taught me such values as endurance, cooperation, getting along with others, and being responsible,” wrote Spencer in his unpublished memoir. Anita Baldwin of Plainville had similar sentiments:

It was hard labor, you got paid almost nothing. But I almost felt like—as an African American person I didn’t have the opportunity of my classmates, who got summer jobs working at some of the retail stores or working at some of the factories…I knew that I had to get an education and have something that I could offer an employer to have a decent job, because just competing with my [white] classmates, I wasn’t getting anywhere.

Seasonal hiring of students was always supplemented with other labor. Growers during World War II looked to Jamaica and the West Indies for help. After the war, Puerto Ricans came to the Hartford area. These groups agitated more strenuously for reform and fair labor practices than the students ever would. Child labor (employing children as young as eight), which became an increasing problem in the 1940s, was not addressed until Connecticut legislation finally passed in 1947 set 14 as the minimum age for farm labor.

What Became of Former Workers?

We now know that many of the students who came north for the summer went on to become prominent and successful individuals, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. being the most noted example. The Luddy-Taylor Tobacco Museum in Windsor holds hundreds of Morehouse employment cards from the Cullman Brothers in the 1930s. A brief search yields a cross-section of future teachers, doctors, lawyers, religious leaders, and other professionals, some of whom returned the North to establish their families.

While not everyone cares to remember their time working tobacco, many people are now beginning to share their experiences. Since 2000, several reunions have been held in Amherst and Nelson counties in Virginia, where more than 2,000 former black high school recruits reconnected. In conversations, these former students have been quick to identify others, better known than they, who also came north to work in Connecticut. The young Arthur Ashe, Mahalia Jackson, Thurgood Marshall, and Hattie McDaniel were named among the thousands of students who, virtually unnoticed at the time, labored in the shade.

Dawn Byron Hutchins is a historian and independent museum consultant.

© Connecticut Explored. All rights reserved. This article originally appeared in Connecticut Explored (formerly Hog River Journal ) Vol. 9/ No. 3, Summer 2011.

Note: ConnecticutHistory.org does not edit content originally published on another platform and therefore does not update any instances of outdated content or language.